From a young age, I’ve always preferred working behind the scenes to centre stage. I left school with a strong ambition to work in costume and set design for film and theatre, but after finding my path in languages and history of art, I realised that there were so many ways to recreate that backstage excitement. Museum translation definitely scratches that itch, and it has come to be one of my favourite disciplines as a creative professional translator. In this article, I take a look at some of the secrets and pitfalls that can make or break a multi-lingual exhibition, with a particular focus on French to English translations.

Source: @chapeau.petrus

Keeping the voice evocative but accessible

Nobody can deny the beauty of the French language. Those who truly master it can push it to its elegant, playful and more abstract limits. This linguistic prowess can make for some beautiful texts, particularly in a museum context, but sometimes as translators we find the need to latch on to something more tangible in order to find the right flow in our translation. English does tend to be punchier and more direct, but this does not mean that any elegance or poetry needs to be lost in the final text.

The main challenge when translating exhibition labels, wall text or brochures from French into English is to grasp the meaning, maintain the style, and transform it into something equally evocative for an English reader. But there is one caveat – exhibition texts are displayed side by side, leaving any translation “exposed”. Delve too voraciously into transcreation, and you may fall prey to the critical eye of any bilingual visitors. Stay too close to the text, however, and you risk producing a rather waffly translation that readers can’t identify with. Museum visitors seek emotional engagement and will rarely have the patience to unravel tangled prose in order to seek meaning. A convoluted text can also be quite alienating for the visitor, leaving them feeling not “smart enough” and with a sense of imposter syndrome.

My solution? Making sure I fully understand what the source is trying to convey and formulating my translation after carefully examining the artwork in question. By forming my own emotional response as a viewer-translator, I can provide a natural sounding translation that is more likely to engage the museum visitor.

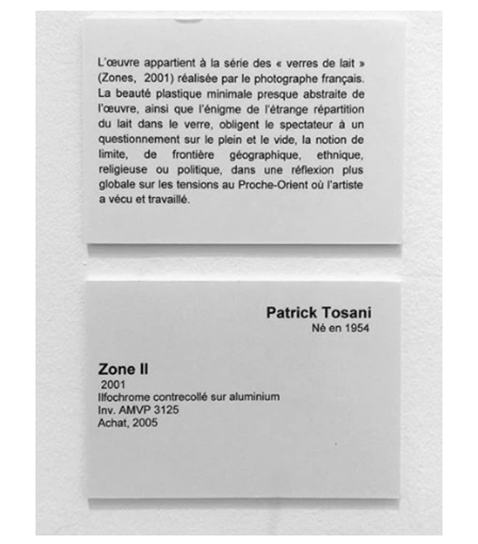

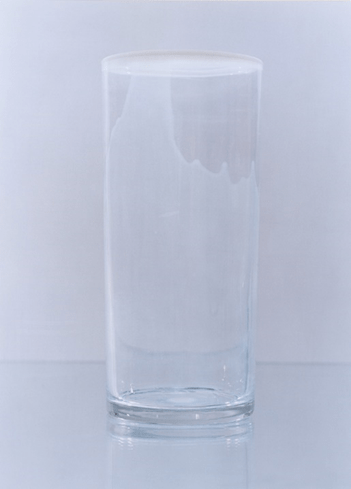

Sometimes, however, we must translate texts on works that do not resonate with us. Let’s look at how we would deal with an extreme case – a simple “glass of milk”, on display at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris:

Here, we may well look at the glass of milk and struggle to connect with it on an emotional level, but duty calls – we must find a way to make our translation as accessible as possible for the museum-goer. The rest is up to them.

I would translate this label as follows:

“This work is part of the French photographer’s “glasses of milk” series (Zones, 2001). The minimalist, almost abstract, plastic beauty of the piece, along with the mysterious positioning of the milk in the glass, forces the viewer to question the notions of negative and positive space, boundaries, and geographical, ethnic, religious and political divides, beckoning a broader reflection on the conflicts facing the Middle-East, where the artist lived and worked.”

Sometimes as translators we must remember that we are not the writer or the artist, and that our role is to simply keep things as clear as possible and faithful to the original, while using language to our advantage to spark an intellectual or emotional response in the viewer.

Telling a story: leaning into the literary

Museum writers are storytellers, and by extension translators must also adopt this role. It is my view that vivid images, sensorial language and clear structure allow for the most engaging explanatory texts in a museum context. Whenever I am sent museum labels or wall texts to translate, I see it as a great opportunity to think creatively and find the right words to capture the viewer’s imagination whilst remaining faithful to the original text.

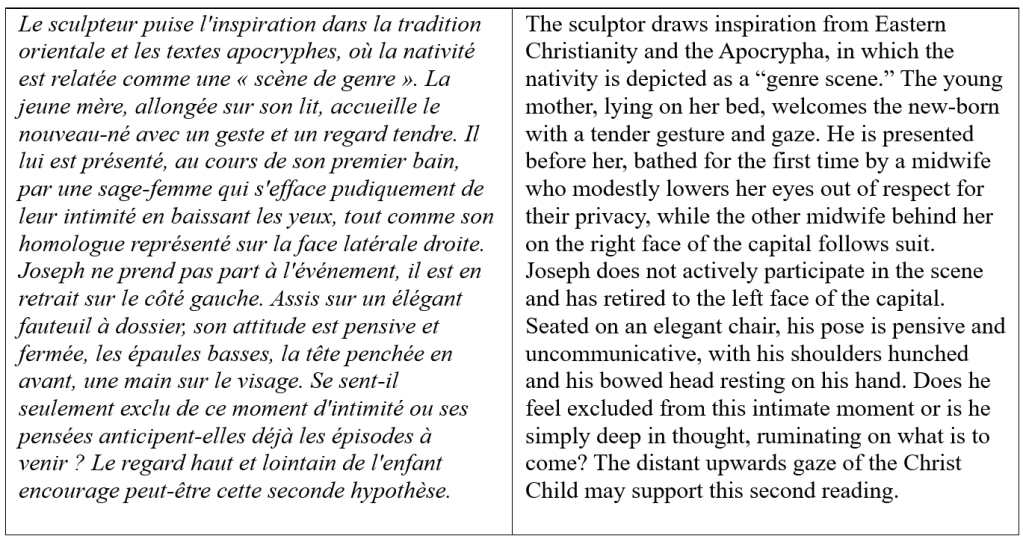

Take this example from my translation of the brochure offered to visitors of Autun Cathedral, which provides explanations of the cathedral’s famous column capitals. As many include complex religious symbols and details barely visible to the naked eye, I aimed for as clear a translation as possible to reflect the source while engaging the listener:

The risks of cutting corners and the AI revolution

Art is the very visual representation of the human experience. It therefore seems logical that those who write about it should be human… Right?

In the current financial climate, cultural projects such as exhibitions run on a tight budget, with little left over to pay for professional translation services. The solution seems simple – to use AI for all exhibition text translations and save a buck or two.

The main issue with this is that AI does not yet understand nuance when it comes to linking a piece of art to its greater emotional and historical context, particularly when this extends beyond a mere recounting of Wikipedia facts. Concepts such as brushstrokes, shade, and iconography are delicate and require specialised knowledge. When dealing with French to English translations, a failure to recognise that “vide” does not always mean “empty”, “plastique” does not always mean plastic, and “attitude” does not always mean “attitude” can result in clunky, disastrous translations that leave the viewer feeling confused, distancing them from the artwork. These subtleties often go unnoticed by a non-native speaker, but once that text is on the wall, the museum’s very credibility is at risk.

For art’s sake…

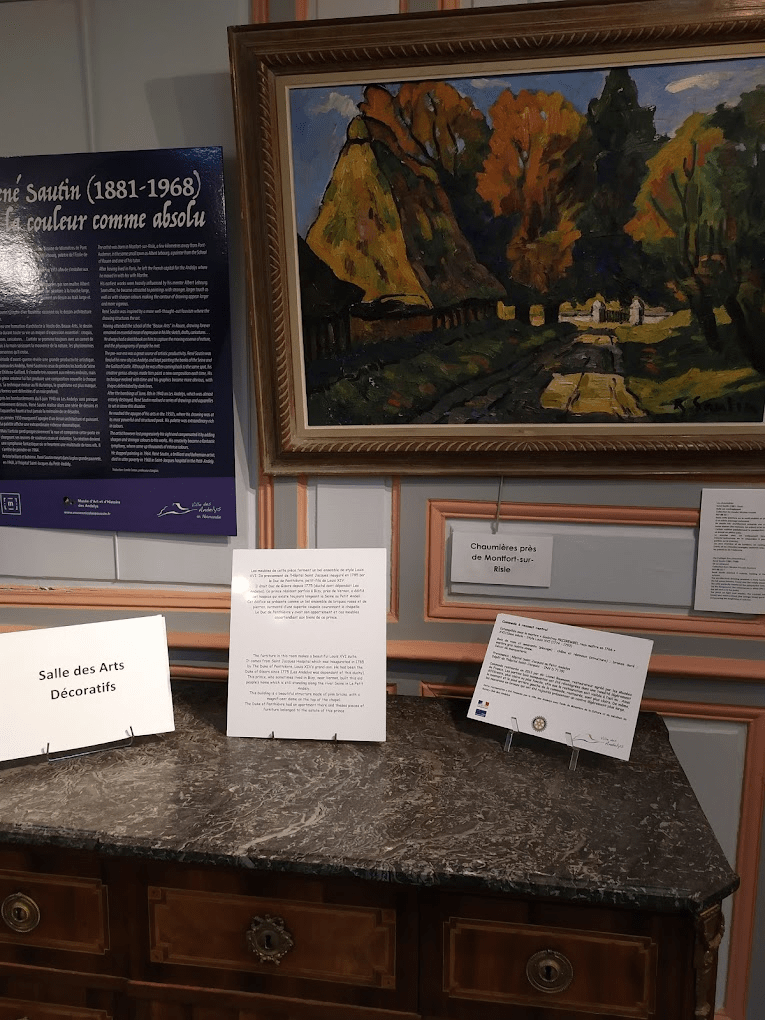

Take it from a totally unbiased bystander: the best thing an art museum can do when trying to retain and attract non-native speakers is to call on the experience of a translator specialising in history of art. Over the years, I have worked on a wide range of translations from both French and Spanish into English specially tailored for a museum context. Drawing on my love of art, my knowledge of art history, and my language skills, providing translations of this type always fills me with joy and a great sense of purpose.

Are you a translator working in the field of museum and art translation or just an art lover? Add me on LinkedIn so we can share our experiences and exhibition recommendations!

Are you a company or individual looking for creative translation services from French or Spanish into English? Contact me for a quote or get in touch to find out more about the freelance translation services I offer.