« Γάλλοι καὶ Γραικοὶ δεμένοι

μὲ φιλίαν ἑνωμένοι,

δέν εἰναι Γραικοὶ ἢ Γάλλοι,

ἀλλ’ ἕν ἐθνος, Γραικογάλλοι »

“The French and Greeks are allies,

united by friendship,

they are not simply the Greeks or the French,

but one single people, the Francogreeks.”

Adamantios Korais, 1800

Of all my expectations coming to Greece as a translator, discovering a shared affinity for the French language was not one of them. Now having recently moved to Athens, I’m starting a new chapter in my language learning journey, and finding connections with my other working languages is helping me to find a sense of community here.

As I explore these busy, chaotic streets from Spanish language bookshops to the Institut Français de Grèce, and as I gradually get to grips with B1-level Greek, I can’t help but notice the tangible presence of French both in the language and the Athenian cityscape itself. After my initial reaction of “Huh, that’s cool!” I did a little digging and uncovered a rich history and lexical tradition unique to this country.

So, with no further ado, here is my little καρτ ποστάλ (carte postale) from Athens to give you a little taste of the κουλέρ λοκάλ (couleur locale)!

Centuries of mutual admiration

According to one study by Sina Ahmadi based on the work of linguist Ilias Konstantinou, French currently represents 18.3% of all loanwords in the Modern Greek language, just after Turkish (21%) and Italian (22.2%). It has also been shown to be its greatest source of semantic loans. There is a long history of contact between the French and Greek languages, two traditions equally steeped in pride and rich history, but it was not until the Enlightenment that this influence truly became apparent. Viewed as the language of Descartes, the language of reason, French’s illustrious reputation remained, and from the 18th to the 20th century, young Greek scholars such as Korais or Psicharis would choose to complete their studies in France, bringing ideas, literature and terminology back home with them.

Furthermore, the Grecomania taking the northern European elite by storm reflected Greece’s own history back at it via the rose-tinted mirror of neoclassicism, further feeding this sense of mutual admiration.

“Greeks were exposed to the Enlightenment mentality by multiple books in translation, newspapers and periodicals. By entering into closer contact with Western Europe, the Greeks also rediscovered the heritage of their own ancestors. The return to Antiquity and the neoclassicism that defined the Age of Enlightenment had repercussions within Greece. A Greek conscience emerged along with a strong interest in the past.”

(quote taken and translated from Tiebout, Miet, L’influence du français sur le grec moderne : le domaine du calque)

In the early 20th century, the forced expulsion of Minor Asian Greeks to Athens and other cities around Greece brought with it a new composite, parallel culture and a new oral tradition. Large numbers of those torn from their homes in Minor Asia were highly educated and multilingual; many were fluent in French, having left behind positions in the diplomatic, administrative, academic and trade sectors. Cities like Smyrna and Constantinople were major trade hubs and cultural melting pots, vestiges of the “multi-confessional, extraordinary polyglot Ottoman world.” As these individuals were forced into urban ghettos in mainland Greece, stripped of their wealth and belongings, this once lofty language saw a certain “fall from grace.”

Culturally rich underworlds began to emerge from these highly marginalised urban centres in Greece. The vernacular of this community seeped its way into rebetiko, a musical genre with deep roots in Minor Asia, which soon gained popularity among the general Greek population. This was a linguistic tradition that greatly featured loanwords not only of Turkish, but also of French origin, and this can still be heard today in the lyrics of early rebetiko.

Not your average Francophile: introducing the ‘mangas’

In the UK, French loanwords are more immediately associated with pretention, the upper class, your Frasier Cranes of the world… Not so much with crime and seedy dealings in smoky basements. In the latter half of the 20th century, however, French, along with Turkish, played a central role in shaping the lexicon of the iconic Athenian gangster and man about town: the “mangas” (μάγκας). In popular depictions, the sharply dressed, komboloi-flipping mangas can often be heard dropping in French loanwords such as σιλάνς (silence, defined by slang.gr as “a more mangas-like yet polite way to say ’shut up’”); αρζαν (argent; money), or ανφάν γκατέ (enfant gâté; spoilt kid).

and knife tucked into the belt.

French loanwords continue to carry this connotation of street smarts and gritty cosmopolitan charm to this day, although the generations that had adopted this style of speaking are slowly dying out, with French loan words competing neck-and-neck with Anglicisms among younger speakers and the chronically online. French words are still commonplace in everyday Greek, often used for 19th or 20th century inventions, words relating to cars and car parts, philosophical concepts, and fashion and beauty terms. For example, when someone is getting ready for a party, they are doing their beauté (μποτέ)!

Case study of French loan words thriving in Modern Greek: a song by Nalyssa Green

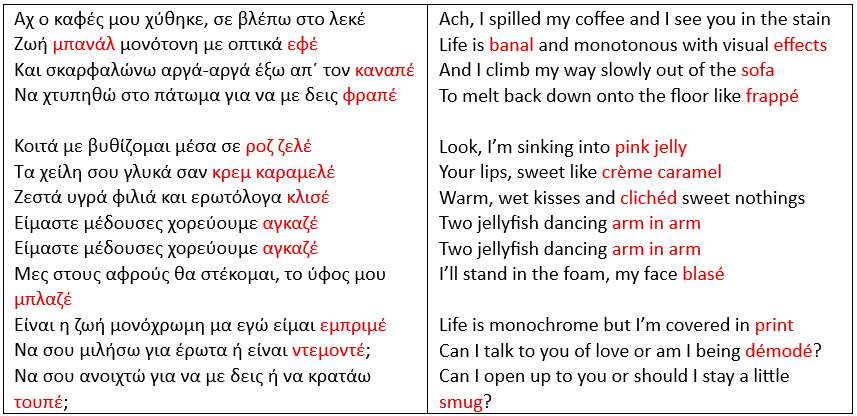

Over the last few months, as I mulled over these connections between these two languages that mean so much to me, I came across a sugary-sweet love song by Athens artist Nalyssa Green. The song is entitled Κρεμ Καραμελέ, “Crème Caramel”—a fittingly nostalgic dessert. Here, we see French loanwords beautifully interlaced with Greek. Let’s take a closer look with my attempt at an English translation (French loanwords shown in red):

Here, in such a short song, we have no less than 12 French loan words, used not only as a rhyming scheme but also as a way of creating rich, nostalgia-coded imagery: μπανάλ (banal), εφέ (effets; effects), καναπέ (canapé; sofa), φραπέ (frappé), ροζ (rose; pink), ζελέ (gelée, jelly), κρεμ καραμελέ (crème caramel), κλισέ (cliché), αγκαζέ (engagé, arm in arm), μπλαζέ (blasé), εμπριμέ (imprimé, printed), ντεμοντέ (démodé), and, rather unexpectedly, τουπέ (toupé) meaning arrogant or bold. One might be tricked into thinking leké (λεκέ, stain) was a French loan word too, but—surprise! It’s Turkish.

These lyrics demonstrate, in its most indulgent form, the Greek affinity for the French language and its power as a stylistic device. Here, and more generally in Greek, we find a predilection for the “é” sound, which us Anglophones can agree does sound pretty classy. Some of these loans conjure up an image of early 20th century Europe, such as the term engagé – in this context, “dancing together” – which I imagine must have stemmed from early dance halls, when someone was “otherwise engaged” on the dancefloor. I can’t help wondering, where does French lie today in the modern Greek psyche—in the smoky, street-smart roots of mangas culture and early rebetiko, or in the dreamy realm of bygone cosmopolitan charm and romance?

Source: LiFO https://www.lifo.gr/various/ayta-einai-ta-kalytera-ton-petralonon

Points of confluence and navigating the Anglo-Franco-Greek space as a translator

This only scratches the surface of the complex world of Modern Greek, so beautifully shaped by all its foreign influences and tumultuous history. From the shop fronts of Athens to the gooey-eyed lyrics of Nalyssa Green, we see exactly how trade, music and migration can smash down the boundaries between foreign languages, defying borders and so-called linguistic purism.

The space I occupy as a translator in this country is equally fluid. While my level of Greek is not yet sufficient for taking on translation projects, I am trying to find my place as a French translator within this new Greek context, and that means sniffing out the niches where my skills might be of use. Wine and gastronomy seem to be an interesting path to explore, as they are so closely interlinked with the largely English-speaking tourism industry and French tradition. Fashion is another interesting point of convergence, and as more and more sustainable clothing brands are coming out of France, I see an excellent opportunity for synergies with small Greek fashion brands, a market that is visibly thriving in the capital. Whether there is any demand here for English translation or copywriting is yet to be seen, but I nonetheless find these crossovers fascinating as a language enthusiast and citoyenne du monde. For now, it’s still early days in this new Greek chapter of mine, so all I can say is watch this space! Σας μερσώ! Ωρέ ντουβάρ!*

Find out more

Curious about which Modern Greek words come from French? Here is a very thorough list of all the most common French loanwords (in Greek and French). I was particularly surprised to find ζαμανφουτισμός (je m’en foutisme) on the list!

Want more information on the Minor Asian Catastrophe and its effects on Greek culture? This blog post by Europeana Subtitled provides a great overview with archive documentary footage subtitled in English.

Liked the look of the vintage shop front photos used in this article and interested in learning more about the shops that define Old Athens? Check out this article featuring some of the familiar faces I see every day around my office in Omonia.

In need of any translation or interpreting services that require extensive knowledge of the French and Greek cultures? Looking for some English language copy to promote your business in France or Greece? I’ve got you covered! Get in touch for more info on my rates and services.

References:

Agravaras, D., “Marking 100 years since the end of the Greco-Turkish war”, published 14/09/2022 on https://www.europeana.eu/en/stories/the-asia-minor-catastrophe (accessed June 2025)

Ahmadi, S., “Foreign loanwords in Modern Greek”, published 18/03/2019 on sinaahmadi.github.io (accessed June 2025)

Coray, A. (Κοραή Α.) Άσμα Πολεμιστήριον των εν Αιγύπτωι περί ελευθερίας μαχομένων Γραικών, Αίγυπτος: Παρίσι (1800)

Fliatouras, A., “Πόσα και ποια δάνεια έχει η σύγχρονη κοινή νέα ελληνική; Μια πρώτη προσέγγιση.” Γλωσσολογία/Glossologia 29 (2021)

Mazower, M. in Shields, S., “The Greek-Turkish Population Exchange” in Middle East Report No. 267 (Summer 2013)

Tiebout, M., “L’influence du français sur le grec moderne : le domaine du calque” (Ghent University, 2009)